- Permbajtja

- prev

- next

- prev

- next

Bauhaus, the visioner behind it, Walter Gropius

by Dajana Shallo, "Thresholds of XX century architecture" EPOKA University

Abstract

An important and influential movement of the 20th century is Bauhaus exploration in architecture, design, visual communication, furniture and appliances. By considering innovation and applied art as a route from modern design of the industrial revolution to functional-design, the Bauhaus expresses the cultural industry. The Bauhaus continues to play a key role in fusing art, technology, and industry. This paper attempts to present the elements defining the philosophical approach, the characteristics and the style of the Bauhaus movement. More specifically, it outlines the scope of the era in which this institution was founded as well as the key figures’ ideologies. This paper focus on the founder and most influential architect and designer of Bauhaus and his architecture and contributions to architecture. It examines how it affected global graphic design, visual communication, and architecture.

Introduction

Paul Klee, a very well known artist from the Bauhaus School, has said that art does not reproduce what we see; rather, it makes us see. According to Klee, an artist’s work of art will stay foreign to them without intuition. An artist’s dedicated work on his crafts relies entirely on the flow of ideas and creativity to produce its craftsmanship. It relies on the process and growth that comes within. The intuition becomes a thought, a thought transforms into ideas, ideas become products of reality and these products flow into movements.

In the production of artistic creation, the means leading to design, where artists and artisans are specialists and professionals in manufacturing forms with a functional goal, Bauhaus is tied to aesthetics and architecture. Its technical characteristics are highlighted by the necessity of these forms.

One of the most crucial responsibilities with regard to Machine aesthetics, Arts and Crafts, and the De Stijl movement is the asymmetrical balancing of elements in relation to new techniques in architectural design and the rationalisation and an aesthetic of the reduction that was notable in Weimar. This was the beginning of Bauhaus, a school of art founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius with an emphasis on social and industrial growth while paying close attention to the technical and practical components. The early 20th century saw a significant impact of the Bauhaus aesthetic and social theory, especially with the introduction of design, which was characterised by compositions and creations in the link between art, technology, and industry. Bauhaus influenced society’s way of life from 1919 to 1920 as a result of housing culture and the social ideal of bringing art to the people.

The goal of this movement was to combine the ideas of form and function to produce a brand-new kind of architecture that was both aesthetically beautiful and useful. The Bauhaus school of architecture was distinguished by its emphasis on mass manufacturing, simplicity, and functionality. This method stood in sharp contrast to the then-dominant elaborate and decorative architectural styles. Walter Gropius, the architect who established the Bauhaus School of Design in 1919, was one of the important figures in the Bauhaus movement. Gropius thought that the secret to designing both aesthetically beautiful and useful architecture was to do away with superfluous adornment and concentrate on the principles of form and function. This strategy was visible in the school’s first building, which Gropius designed and was distinguished by its straightforward and unadorned style.

The Bauhaus movement had a significant impact on architecture, and many contemporary structures still bear the effects of this style today. The modernist movement, which strove to design structures that were practical, effective, and aesthetically beautiful, was made possible by the movement’s emphasis on simplicity and practicality. Additionally, because of the Bauhaus movement’s emphasis on mass production, new building methods and materials were created, enabling structures to be built more swiftly and effectively. Bauhaus architecture is now regarded as a significant architectural movement, and its guiding principles continue to influence and inspire architects all over the world.

The Evolution of Bauhaus

Gropius rooted the Bauhaus’ quest for a new society and a new kind of citizen in earlier attempts to humanize industrial production from the outset. The arts and crafts movement of William Morris and John Ruskin had a significant influence on the Bauhaus. Morris and Ruskin embraced handcraft, practical design, and luxurious, frequently handmade materials in an effort to counter the alienating consequences of industrialization. While Gropius recognized the value of combining art and craft to enhance daily living, he equally praised the machine and the factory.

Gropius belonged to the Deutscher Werkbund before enrolling at the Bauhaus.a group of businessmen, designers, and artists who worked to enhance the appearance of ordinary objects utilizing mechanized production in order to give common people access to products of the greatest quality. Industrial innovations, according to Gropius, might revolutionize manufacturing by enabling artists to create. By making this work accessible to regular people, it could change how people consume. In a nutshell, machines might be democratic empowerment instruments.

The visioner behind Bauhaus

In general, strategy refers to the process of identifying distinctions between circumstances and selecting a course of action based on those circumstances or context. A type of strategic approach is to recognize that situations can’t always be the same and to act in accordance with shifting ideas. Strategy is a dynamic strategy that can demonstrate differences with the process, not a closed approach or finished conclusion. For Bauhaus, creativity has always been of utmost importance. Being effective at work has been linked to enhancing students’ creative abilities. It has been the goal of the academic program to highlight and foster innovation. To actually grasp what is explained in Bauhaus classes, consider their differences. Is a method of seeing and questioning something. In actuality, such a contrast created the groundwork for the Bauhaus.

In the Proclamation of the Bauhaus (1919), Gropius imagined a utopian craft guild fusing architecture, sculpture, and painting into an unified creative expression. This vision for an unification of art and design was first articulated in the writings of Gropius. A craft-based curriculum was created by Gropius to produce designers and craftspeople who could produce functional and beautiful products that suited this new way of life. In the Bauhaus, both fine arts and design education were united. In order to prepare the students for more specialised studies, the curriculum started with a foundational course that involved the students—who came from a variety of socioeconomic and educational backgrounds—in the study of materials, colour theory, and formal relationships. Visual artists like Vasily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, Paul Klee, and others frequently instructed this introductory course.

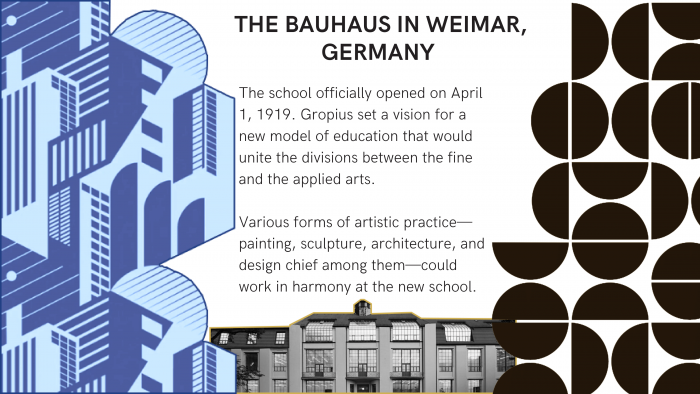

The Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany

The former Grand-Ducal Saxon College of Fine Arts Art School in Weimar appointed Walter Gropius as its director. He legally combined it with the defunct College of Applied Art, renaming the new school the State Bauhaus in Weimar. The national assembly that met in Weimar at the time to draft the 1919 constitution epitomised the spirit of awakening that was prevalent in the current politics and was represented by the school. High calibre painters like as Gerhard Marcks, Lyonel Feininger, Johannes Itten, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky, and László Moholy-Nagy were chosen by Gropius to serve as masters at the Bauhaus Weimar.

The students next entered specialized workshops where they learned about metalworking, cabinetmaking, weaving, pottery, typography, and wall painting after being fully immersed in Bauhaus doctrine. Although Gropius’ original goal was to unite the arts via craft, some components of this strategy proved to be financially unviable. In 1923, he repositioned the objectives of the Bauhaus while keeping the focus on craft and highlighting the significance of designing for mass manufacturing. The phrase “Art into Industry” was adopted by the school at this point.

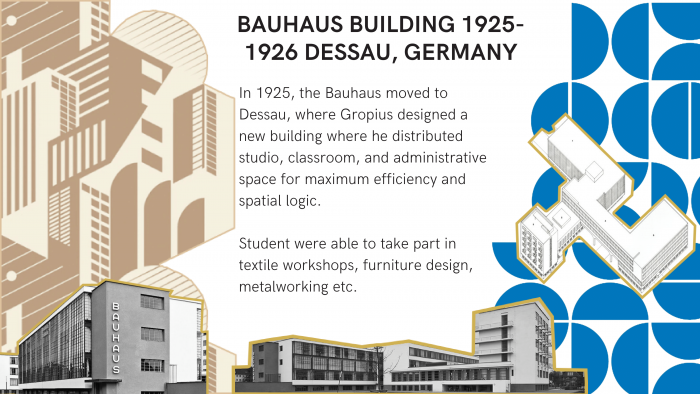

Bauhaus Building Dessau, Germany

Gropius had a blank canvas to work with when the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to the industrial city of Dessau. This allowed him to create a campus that reflected the values of the school. The buildings are all geometric in design and use modern industrial materials like reinforced concrete. They also all have flat roofs. Gropius expanded ideas previously cultivated in the Fagus Factory in Saxony. Each room was also thoughtfully designed to represent its purpose. The three-story workshop wing has a glass curtain wall supported by a steel framework that ensures workshops are well-lit and conveys the idea that the school serves as an experimental laboratory for cutting-edge technologies and creative methods.

The workshop wing’s interiors were created to be open and to promote communication and movement, while huge areas had movable partition walls to allow for flexible learning. The whole interior decor was created and manufactured in the Bauhaus workshops, fostering a sense of community and departmental cooperation.

The junior masters and students were housed in 28 studio apartments with little cantilevered balconies on the fifth floor of a five-story building. Gropius created homes for the Bauhaus Masters and their families away from the main site. Gropius originally intended to construct these totally out of prefabricated parts, but due to technological limitations, this plan was only partially carried out. The homes of The Masters are constructed of interconnecting cubes of varying heights, and each one has a studio with a balcony and big windows.

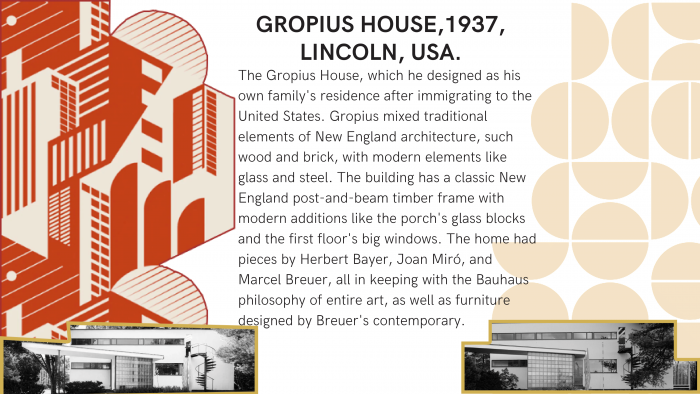

Gropius House

The Gropius House, which he designed as his own family’s residence soon after arriving in America, had a significant impact in popularising modernist architecture outside of Europe. Gropius mixed traditional elements of New England architecture, such wood and brick, with modern elements like glass and steel. The building has a classic New England post-and-beam timber frame with modern additions like the porch’s glass blocks and the first floor’s big windows. The home had pieces by Herbert Bayer, Joan Miró, and Marcel Breuer, all in keeping with the Bauhaus philosophy of entire art, as well as furniture designed by Breuer’s contemporary.

Gropius planned the house to be straightforward and effective, and to first and foremost meet the needs of his family on a daily basis, just like he did with his previous designs for factories and industrial structures. The connections between the indoor and outdoor areas, as well as functional additions like the inclusion of built-in storage and a separate entry for his adoptive daughter, are examples of this. Gropius created a connection between the structure and the site by generating multiple zones on the surrounding property as well as spatial awareness within the house. The Gropius House served as the architect’s best opportunity to get known and establish his name in the country.

The Aftermath of Bauhaus

The majority of the Bauhaus teachers and pupils emigrated to the country and enrolled in prestigious universities. Gropius and Breuer taught at Harvard, Mies attended the Illinois Institute of Technology. They actively spread the Bauhaus aesthetic in their new setting. Many Jewish Bauhaus students traveled to Israel and helped develop the “White City,” where now there are approximately 4000 structures in the Bauhaus style in Tel Aviv. A lesson for all design schools of the present and the future can be learned from the idea of integrating a college with a feeling of common purpose and shared ideas - creating a strong ideology that can translate and transcend to the invisible features of campus, curriculum, and dialogues. Even today, the Bauhaus is still relevant because it shows how design and life can become synonymous and how all educational institutions struggle to find the best faculty members while maintaining their mission in the face of bureaucratic obstacles.

The legacy of Walter Gropius

Gropius’ most important contributions were as an educator, even though he is most known for advocating architectural mass production methods and for being a major player in introducing modernist architecture to the United States. The Bauhaus questioned and reimagined how art, design, and architecture were taught, moving toward a more collaborative and multidisciplinary mode of operation and incorporating technical innovation and mass production techniques into the curriculum.

In addition, despite only existing for a little over ten years, it brought together a remarkable and incredibly significant collection of professors and artists who collaborated and together produced a lasting legacy. Gropius played a key role in creating this method and in advancing it through his teaching in the United States. In order to honor this heritage, Gropius and Herbert Bayer co-curated the retrospective exhibition Bauhaus 1919–1928 in 1938 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Conclusions

The influence of the Bauhaus is still evident today, even on the floors of furniture shops. The geometric modernism of Bauhaus teapots and lamps has become so ingrained in our culture that we are no longer aware of its origins, if they even have any.

Though few people today may be familiar with the Bauhaus as an actual organisation, its guiding principles nevertheless permeate modern culture. Creativity, cooperation, innovation, and design are the guiding principles of global higher education and the business world. The type of multidisciplinary education that the Bauhaus pioneered is now widely used, not just for artists but also for engineers, marketers, computer scientists, and product designers. The dream that inspired the Bauhaus is now a reality: combining work and pleasure and making the workplace a model of an equitable community.

The Bauhaus art movement is a precursor to modernism and is distinguished by its emphasis on geometric design, regard for useful materials, and strict economic sensitivities. According to Bauhaus theory, logical design in terms of methods and materials should just be the beginning of the process of creating a fresh, contemporary understanding of beauty. I can recognize the Bauhaus’ distinctive features in modern designs with ease now that I’ve learned about them. I believe it to be a timeless fashion that can be worn in a variety of ways. It’s a novel technique to draw attention, even from those who are unaware of the Bauhaus.