- Permbajtja

- prev

- next

- prev

- next

HIGHLIGHT: ROBIN BOYD

Backround and early life

Robin Gerard Penleigh Boyd (3 January 1919 – 16 October 1971) was an Australian architect, writer, teacher and social commentator. He, along with Harry Seidler, stands as one of the foremost proponents for the International Modern Movement in Australian architecture. Boyd is the author of the influential book The Australian Ugliness (1960), a critique on Australian architecture, particularly the state of Australian suburbia and its lack of a uniform architectural goal.

Like his American contemporary John Lautner, Boyd had relatively few opportunities to design major buildings and his best known and most influential works as an architect are his numerous and innovative small house designs.

Robin Boyd was a scion of the Boyd artistic dynasty in Australia, and his extended family were involved painters, sculptors, architects, writers and others in the arts. Robin was the younger son of the painter Penleigh Boyd, and his own son, named after his grandfather Penleigh, is an architect. He was a nephew of author Martin Boyd and a first cousin of Australian painter Arthur Boyd and his brothers David and Guy. In 1938 his grandfather Arthur Merric Boyd offered him his first commission, a studio for Arthur Boyd on the Boyd property.

Robin's Queensland-born mother, Edith Susan Gerard Anderson, was herself a skilled painter who also came from a prominent family.

Robin Boyd and his older brother Pat spent their early childhood at 'The Robins', the family home and studio that his father had built on land he purchased near Melbourne but in 1922 Penleigh sold 'The Robins' and moved his family to Sydney. Soon after arriving, he was enlisted by Sydney Ure Smith as one of the organisers of a major exhibition of contemporary European art. Penleigh took his family with him to England late in the year to pick paintings; he returned to Sydney without them in June 1923 to set up the exhibition, which was staged in Sydney and Melbourne during July–August.

After Penleigh's death Edith and the boys lived for a time in rented premises in upperclass Toorak and Robin's first two years of schooling were at Glamorgan Preparatory School. Edith bought a modest house in East Malvern in 1927, when Robin was enrolled at the nearby Lloyd Street State School. As a schoolboy he read widely and became an avid fan of films and jazz music. In 1930 he moved on to the Malvern Church of England Grammar School, where he completed his schooling. He sat for his Leaving Certificate in 1934 and although he failed one subject (Commercial Principles) at the first attempt, he passed that the following year. He had evidently decided quite early on architecture as his chosen career so his mother arranged for him to be articled to leading Melbourne architect Kingsley Henderson. He served in Papua-New Guinea during World War II and resumed his architectural career in 1945.

Architectural career

Boyd first came to notice in the late 1940s for his promotion of inexpensive, functional, partially prefabricated homes incorporating modernist aesthetics. Most of his architectural output was residential, although he also designed some larger buildings including the Domain Park residential tower block and the John Batman Motor Inn in Melbourne and the Australian headquarters of the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust in Canberra, on which he was working at the time of his death.

Boyd was the first Director of the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects Small Homes Service from 1947 to 1953 and for many years from 1948 he was the editor of this service for The Age newspaper, for which he also wrote weekly articles. The Small Homes Service provided designs of inexpensive houses, which attempted to incorporate modern architectural aesthetics and functional planning and were sold to the public for a small fee, and through this work Boyd became a household name in Victoria.

In 1948 Boyd was the recipient of the RVIA Robert and Ada Haddon Travelling Scholarship. The scholarship gave Boyd his first opportunity to travel through Europe which would have a profound influence on his later work.

In 1953 he formed a partnership with Frederick Romberg (1910–1992) and Roy Grounds (1905–1981); their influential Melbourne firm became a significant force in Australian architecture and through the 1950s and 1960s Boyd developed a number of important houses in the regional style, including a 1952 Canberra house for Australian historian Manning Clark.

Boyd was a prolific architect, with over 200 designs to his credit in his relatively short career. He was the sole designer of most of these projects although a number of early commissions were jointly designed with his unofficial partners Kevin Pethebridge and Frank Bell (1945–47) and others were jointly designed with his partners Grounds and Romberg (1953–62). After the acrimonious departure of Grounds from the practice in 1962, Romberg continued in partnership with Boyd until the latter's death.

Boyd was equally prolific and influential as a writer, commentator, educator and public speaker, vehemently supporting modernism in his The Australian Ugliness (1960) with a condemnation of visual pollution and vulgar 'featurism'. His work was documented and promoted by photographers Mark Strizic and Wolfgang Sievers, then the most prominent in their field. For many years from 1947 he was director of The Age Small Homes Service and influenced many people with his popular weekly articles on the subject. He was also lecturer in architecture at the University of Melbourne, and in 1956-57 he took up a teaching position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston offered by Walter Gropius, a friend of Boyd's and a Director at MIT.

Boyd was close friend of satirist Barry Humphries and wrote the liner notes for Humphries' first commercial recording, the EP Wild Life in Suburbia (1958).

Boyd wrote nine books. His groundbreaking Australia's Home (1952) was the first substantial historical survey of Australian domestic architecture, and his best-known and most influential work, The Australian Ugliness (1960) was a popular and outspoken criticism of prevailing establishment tastes in architecture and in popular culture. Boyd was a dogged critic of the decorative tendency that he dubbed "Featurism", which he described as:

... not simply a decorative technique, it starts in concepts and extends upwards through the parts of the numerous trimmings. It may be defined as the subordination of the essential whole and the accentuation of selected separate features.

In 1967 Boyd presented the Boyer Lectures, which were broadcast nationally on ABC Radio. He delivered five lectures on a variety of topics and issues relating to Australia, architecture and design and prevailing cultural values of the time, under the series title Artificial Australia.

He was awarded the Royal Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal in 1969.

Death and legacy

Boyd travelled overseas in April–May 1971, when he contracted an infection and on his return to Australia his doctor detected a heart murmur. In early July his condition worsened and he was admitted to St Andrew's Hospital in Melbourne; he was diagnosed with interstitial pneumonia, told that the infection had settled in one of his heart valves and administered massive six-hourly doses of ampicillin. He recovered somewhat and struggled on through August–September, maintaining his usual heavy work schedule, but in early October his condition deteriorated again and he was admitted to the Royal Melbourne Hospital. Doctors puzzled over a diagnosis but eventually decided to extract all his teeth under full anaesthetic, believing the infection had settled there. He suffered a stroke while recovering from the operation, and although he briefly rallied enough to recognise his wife Patricia, he died three days later on 16 October 1971, aged 52.

In 2005 the not-for-profit Robin Boyd Foundation was established by a group including Boyd's family, the Australian Institute of Architects (Victoria Chapter), the faculties of architecture at the University of Melbourne, Deakin University and RMIT University, and others with expertise, interest and commitment to the advancement of design. Their website lists the Foundation's aims, which are to deepen understanding of the benefits of design through design awareness, design literacy and design advocacy.

Projects

Every house designed by Robin Boyd has a signature idea. Some of these ideas are bolder than others. Some are one-off instances but more often than not, Boyd houses are an intriguing combination and iteration of several themes that he’d been exploring in several houses either before or in tandem with others. That’s the way that most architects work – every commission is a work in progress that begets another and then another. With Boyd, the magic lies in the way that he designs so that no one house is really like any other but you can detect a lineage that at every moment speaks of experimentation and opportunity. In 1956, in an article in The Architectural Review titled “The Functional Neurosis,” Boyd wrote of this controlling idea:

What matters in terms of art is whether the idea is developed consistently enough to permeate the entire work. And what matters to the spirit of architecture is the extent to which the development of the idea exploits the qualities of space and enclosure.

-Blott House

Completed in 1956, this house encapsulates Robin Boyd’s fascination with “the conflict between the opposed desires of privacy and freedom” and stands as a testament to his forward-thinking ideas.

The Blott House at Chirnside Park, completed in 1956 and never before published with photographs, is one of those houses. Today, just over sixty years later, it feels as fresh as it proudly was in Melbourne’s Olympic year.

-King House and Studios (1952-1964)

Designed for a sculptor and an artist and built in three stages, the King House and Studios in Warrandyte “does not easily imply domesticity”. The original one-room house includes a raised bay to the north labelled a “painting platform” and an underfloor space labelled a “food store” that has also been used as a workspace and studio, as well as a small bathroom, a porch and a bedroom that isn’t used as such. “The architecture of this house is flexible, affordable and inherently sustainable due to its longevity and adaptability”.

-Lyons House (1967)

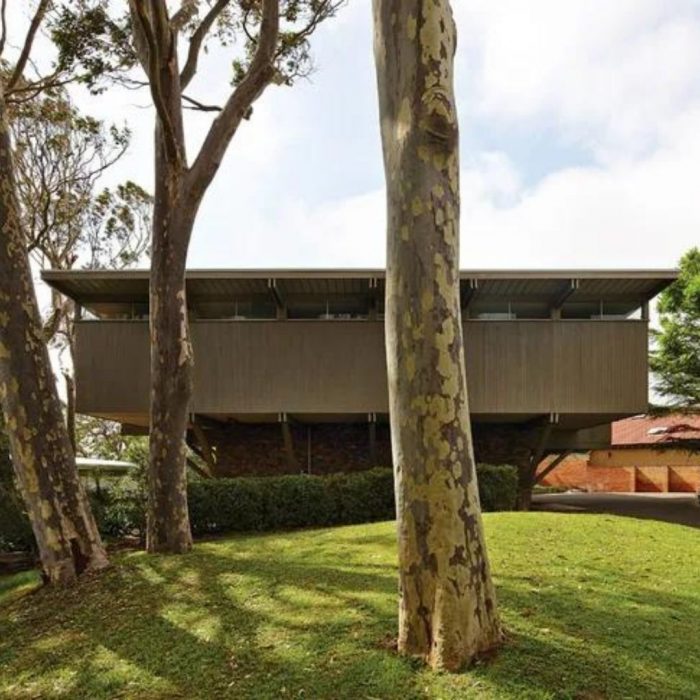

The commission for Robin Boyd’s only Sydney project came from a reader of The Australian Ugliness. A young orthopaedic surgeon, Bill Lyons wanted a Spanish-style courtyard house with a swimming pool. The house Boyd delivered is as requested, albeit raised dramatically off the ground and appearing to cantilever on improbably narrow timber struts.

-Stone House (1953)

Designed in 1953 by Robin Boyd for Victor and Peggy Stone, this modest home in Melbourne’s Eaglemont reflected the progressive attitudes of its owners. The original brief was very simple: a modest dwelling for a couple that intended to have children, with light, greenery and open space. The design reflected the progressive attitudes of its owners: it debunked traditional notions of generational and gender segregation.