- Permbajtja

- prev

- next

- prev

- next

The mission of an architect is to help people understand how to make life more beautiful, the world a better one for living in, and to give reason, rhyme, and meaning to life.

– FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, 1957

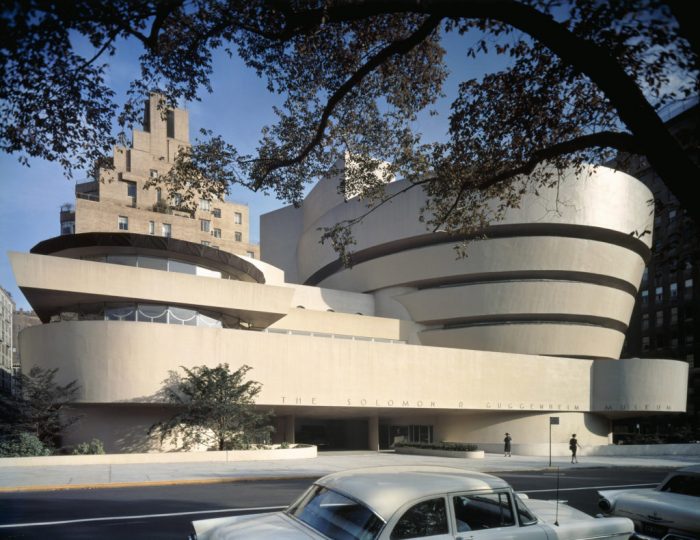

It is very interesting that some projects always accompany you during your student and professional life.I remember quite vividly the first time the image of a beautiful, white, smooth and very harmonic building appeared at the History of Architecture class during my university studie. It was the Guggenheim Musseum in New York.

This month I had the privilege visit that building, impressed in my memory for such a long time and the experience was quite magic!

As I was going up and down the famous ramp that in itself is the museum display ( quite genius at the time ) and definitely I wanted to know more about the architect who projected this grandiose building very atypical at the NewYork scene in those years and what inspired him.

This is why this week the architect of the highlight section is Frank Llloyd Wright, who is considered one the greatest American Architect of all the time.

Photo by N.Hajdini

Who is Frank Lloyd Wright?

Frank Lloyd Wright is considered the father of the architectural movement that aim to create a new architecture for America, free from the European reminiscence that suited the modern American society and way of living.

Over the course of his 70-year career, he designed 1,114 architectural works of all types — 532 of which were realised and became one of the most prolific, unorthodox and controversial masters of 20th-century architecture.

Realizing the first truly American architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses, offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels and museums stand as testament to someone whose unwavering belief in his own convictions changed both his profession and his country[1].

He was destined to be an architect, as his mother projected this desire since she was pregnant and deocrated his nursey with with engravings of English cathedrals to inspire him.

A college dropout, (he studied civil engineering but left 3 months prior to his graduation ) his formation as an architect came largely throughout apprenticeship under his mentor, the Chicago architect Louis Sullivan (Forms follow function). But Wright had innate gifts: a powerful ability to visualise in three dimensions, skill in drawing and a critical and curios mind.[2]

His work developed in different two different phases, starting with the embrace the Art and craft movement to create high-level craft culture through usage of traditional materials and than facing the need to create more affordable houses, usage of new materials ( concrete) and the technological developments such the invention of the automobile :

There are two main styles that he developed thought his career:

The prarie style & Usonian style both of them evolving under his philosophy of Organic architecture

The prarie style

The Prairie style emerged in Chicago around 1900 from the work of a group of young architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright. These architects melded the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, with its emphasis on nature, craftsmanship and simplicity, and the work and writings of architect Luois Sullivan.Wright, inspired by his mentor Louis Sullivan aimed to create a new architecture, detached from the European style that reflects the American modern way of living and that emerges from the American landscape and culture.[3]

In 1893, Frank Lloyd Wright founded his architectural practice in Oak Park, a quiet, semi-rural village on the Western edges of Chicago. It was at his Oak Park Studio during the first decade of the twentieth century that Wright pioneered a bold new approach to domestic architecture, the Prairie style. Inspired by the broad, flat landscape of America’s Midwest, the Prairie style was the first uniquely American architectural style of what has been called “the American Century.”[4]

A series of project of houses were designed by Wright in search for the components that would assemble The Prairie style. These houses reflected the long, low horizontal prairie on which they sat with low-pitched roofs, deep overhangs, no attics or basements, and generally long rows of casement windows that further emphasized the horizontal theme.[5]

Some of Wright’s most important residential works of the time are:

The Darwin D. Martin House in Buffalo, New York (1903),

The Martin House is considered among the most important designs of Wright’s career and is the largest and most highly developed Prairie house on the east coast.

The Martin House was originally part of a larger estate that Wright designed as a series of connected buildings. Aside from the two main residences for Darwin and his brother-in-law, George Barton, the property included a long pergola with a conservatory, a carriage house-stable and a gardener’s cottage, all of which were demolished in 1962 and reconstructed in 2007. Wright was especially proud of the complex, deeming it “a well-nigh perfect composition.”

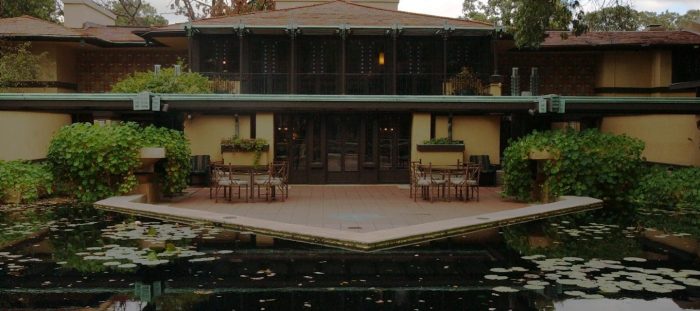

The Avery Coonley House in Riverside, Illinois (1907),

This elaborate Prairie style residence, with its Coach House, Gardener’s Cottage and accompanying gardens, marks the first time that Wright used “zoned planning.” This approach involves dividing spaces based on their function and he would use it for the rest of his career.

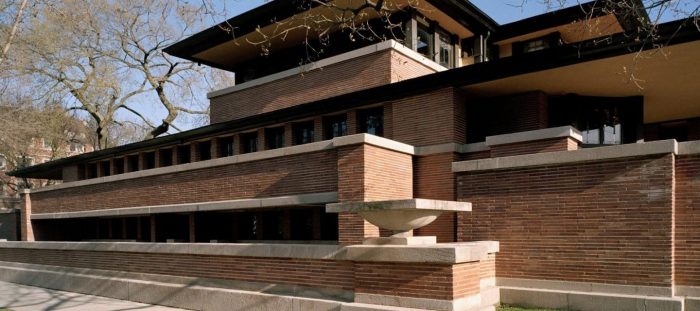

Frederick C. Robie House in Chicago (1908)

Designed as two large rectangles that seem to slide past one another, the long, horizontal residence that Wright created for 28-year-old Frederick Robie, boldly established a new form of domestic design: the Prairie style.

As the first uniquely American architectural style, it responded to the expansive American plains by emphasizing the horizontal over the vertical. A dramatic 6 m cantilevered roof shades ribbons of art-glass windows below creates privacy and seamlessly connects the interior and exterior. Inside, the typical warren of rooms is discarded for a light-filled open plan, centered around a main hearth. Wright responded not only to the openness of the American landscape, but also to the more informal quality of the modern American lifestyle. The Robie House’s influence on American architecture was immediate and undeniable.

“Ever since his address ‘The Art and Craft of the Machine’ (1901), Wright had recognized that it was the destiny of the machine to bring about a profound change in the nature of civilization. His initial reaction, lasting until 1916, had been to adapt the machine to the creation of a high-level craft culture, that is, to apply it to the direct formation of his Prairie Style. Despite the fact that, for Wright, ‘machine’ expression always seemed to involve a certain rhetorical use of the cantilever (the Robie House of 1909 is a typical example), he still insisted on the ultimate authority of traditional materials and methods.”[6]

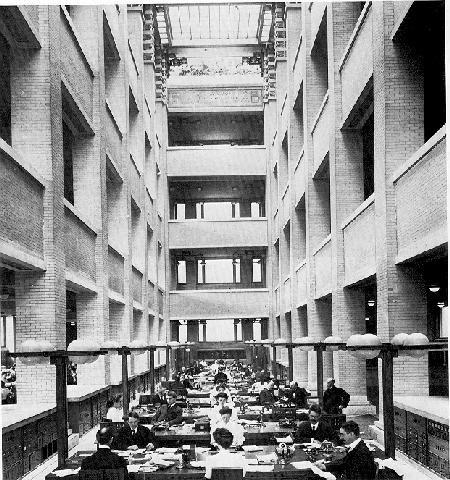

The Larkin Company Administration Building in Buffalo (1903, demolished 1950)

A five-story red brick ode to productivity, Wright’s first major public work was widely heralded in Europe.

Built to serve as the administrative headquarters for the Larkin Company’s burgeoning mail-order soap business, the building was necessarily sited amidst a tangle of railroad lines. To protect its workers from the smoke-laden environment, Wright’s six-story building turned inward, with a Roman-style atrium and surrounding inward-facing balconies creating a bright and airy interior.

Though the Larkin building is now celebrated for its avant-garde vision, Wright’s defiant departure from the popular Beaux-Arts style made it appear “a monster of awkwardness” to many of his contemporaries, such as the hard-hitting Architectural Record critic, Russell Sturgis. Despite being demolished in 1950, the Larkin Building remains a modern icon of twentieth century building.

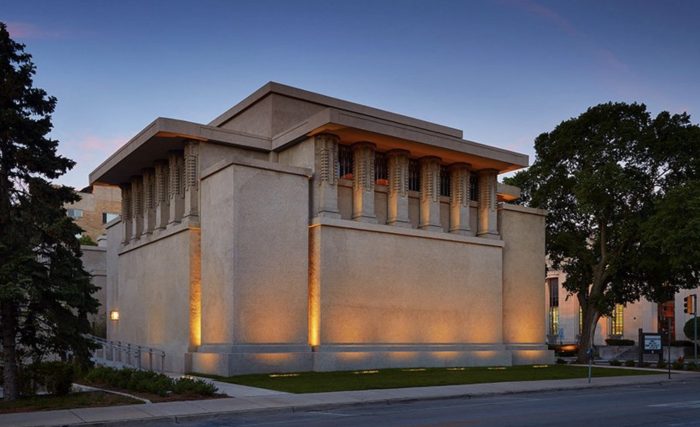

Unity Temple in Oak Park (1905)

Now Wright’s only remaining public Prairie-style building, Unity Temple came with several challenges: a $45,000 budget (one third of the cost of the neighborhood’s typical Gothic edifice), a small, narrow site on a busy main street, and the need to provide two different spaces, one for worship and one for socializing. Wright’s solution used poured-in-place reinforced concrete—a material thus far reserved for factories and warehouses—to create a church that was unlike any other house of worship before

Wright would seek to build “a temple to man, appropriate to his uses as a meeting place, in which to study man himself for his God’s sake.” Wright’s choice of concrete kept costs to a minimum while enabling the façade’s ornament to be cast in, rather than applied afterwards at additional cost. To reduce the noise from the street windows were eliminated at street level. Instead, stained glass skylights and clerestories provided light to the space in green, yellow and brown tones in order to evoke the colors of nature.

Wright designed two separate high, skylit spaces—one for worship, Unity Temple, and one for the congregation’s social gatherings, Unity House—connected by a low, central entrance hall.

Usonian style

Responding to the financial crisis of 1929 and ensuing Great Depression that gripped the United States and the rest of the world, Wright began working on affordable housing, which developed into the Usonian* house.

Wright’s Usonians were a simplified approach to residential construction that reflected both economic realities and changing social trends. In the Usonian houses, Wright was offering a simplified, but beautiful environment for living that Americans could both afford and enjoy. Wright would continue to design Usonian houses for the rest of career, with variations reflecting the diverse client budgets.[6]

The term ‘Usonia’ to denote an egalitarian culture that would spontaneously emerge in the United States. By this he seems to have intended not only a grassroots individualism but also the realization of a new, dispersed form of civilization such as had recently been made possible by mass ownership of the automobile.

Wright’s Usonian vision, first crystallized in his masterworks of the mid-1930s, attained its fulfilment in his Guggenheim Museum, New York, of 1943[7]

Some of the most importat projects are :

Fallingwater, the country house for Edgar Kaufmann in rural Pennsylvania;

Aflex house

The Herbert Jacobs House (the first executed “Usonian” house) in Madison.

John Storer House

Johnson Wax Administration Building in Racine,Wisconsin

Bernard Schwartz House

Guggenheim museum

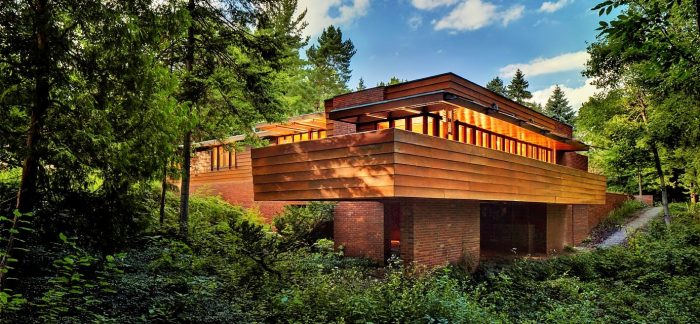

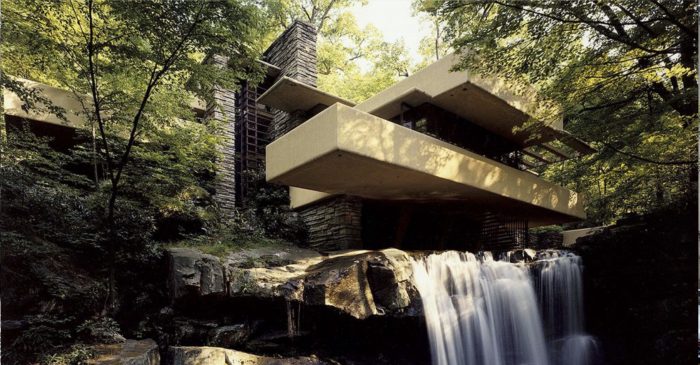

Fallingwater, the country house for Edgar Kaufmann in rural Pennsylvania;

Fallingwater, the country house for Edgar Kaufmann in rural Pennsylvania;

Fallingwater is Wright’s crowning achievement in organic architecture and the American Institute of Architects’ “best all-time work of American architecture.” Its owners, Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann, were a prominent Pittsburgh couple, reputed for their distinctive sense of style and taste.

Photo: Andrew Pielage / Courtesy of Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

In Fallingwater, Wright anchored a series of reinforced concrete “trays” to the natural rock. Cantilevered terraces of local sandstone blend harmoniously with the rock formations, appearing to float above the stream below. The first floor entry, living room and dining room merge to create one continuous space, while a hatch door in the living room opens to a suspended stairway that descends to the stream below. Glass walls further open the rooms to the surrounding landscape. In 1938, Wright designed additional guest quarters set into the hillside directly above the main house and linked by a covered walkway. Fallingwater remained the family’s beloved weekend home for 26 years.

Aflex house

This building, exemplary of Wright’s Usonian style, represents the architect’s answer to low-cost housing for the average American.The one-story structure eliminates the attic to cut down on unusable space, save money, and echo the horizontality of the plains of the American Midwest. In radical opposition to the typical style of the day, its kitchen, living and dining rooms merge to form one unified space, with large windows further enhancing the open living that Wright promoted. The main living space spans a 12 m ravine, and is anchored to the hill by the bedroom wing that culminates in a ground-level master suite.

John Storer House

One of four Mayan Revival-style textile block houses that Wright built in Southern California between 1922-1934, the Storer House is notable for its richly textured concrete walls and is the only of its kind to employ multiple patterns on its blocks (four in all).

Seeking an inexpensive and simple method of construction that would enable ordinary people to build their own homes, Wright developed a modular construction system in which concrete blocks were tied together by steel rods. He believed that this “Textile Block System” achieved an utterly modern and democratic expression of his organic architecture ideal. Built on a steep hillside in the Hollywood Hills, the Storer House was compared to a Pompeiian villa at the time of its construction. Lush landscaping further enhanced its exoticism, providing an illusion of a ruin barely visible within its jungle environment. The residence later fell into Pompeiian-like disrepair, until Hollywood movie producer, Joel Silver—current owner of Wright’s Auldbrass Plantation in South Carolina—purchased the house and undertook an extensive restoration project in 1984. The Storer House, thanks to help from Wright’s grandson Eric Lloyd Wright and the Los Angeles Conservancy, is now widely considered the best-preserved Wright building in Los Angeles. The residence was sold in 2002 and it remains a private residence.

Johnson Wax Administration Building in Racine,Wisconsin

When the Johnson Wax Administration Building was completed Life magazine called it the greatest innovation since the skyscraper: “a truer glimpse of the shape of things to come.” Like Wright’s Larkin Administration building of 1903, Wright desired to build an exhilarating work environment, even suggesting that it be moved out of the bleak industrial zone of Racine for which it was planned.

When Herbert Johnson refused to turn his back on his company’s hometown, Wright designed the building without windows, explaining that as “nature was not present” in the environment, his design would “recreate nature” on the interior. The result, Wright promised, would be like working in a pine forest glade, with fresh air and sunlight all of the time. Wright achieved his vision with the help of two important innovations: steel mesh-reinforced concrete and glass tubing. The concrete allowed him to build slender white columns that rose tendril-like from their nine-inch bases to eighteen-foot-wide circular concrete “lily pads” that support the roof. The tubing allowed much of the roof and clerestory to filter perfectly diffuse light between the lily pads, creating a space that, without traditional windows, is the very essence of light. Due to the fact that the available technology could not properly seal the glass tubing, the roof leaked every time it rained.

The Herbert Jacobs House

Challenged by Herbert Jacobs to create a decent home for $5,000, Wright’s design for “Jacobs I” (as it came to be known) is widely considered to be Wright’s first Usonian structure.

Wright’s Usonian houses related directly to the earth, unimpeded by a foundation, front porch, protruding chimney, or distracting shrubbery. Glass curtain walls and natural materials like wood, stone and brick further tied the house to its environment.

The Herbert Jacobs House became the prototype home for Wright’s dream vision for a utopian urban development, Broadacre City. The house’s open arrangement of living room, dining room and kitchen was also later adopted in the ranch style houses that populated post-war American suburbs, underscoring the building’s historical significance.

Bernard Schwartz House

In Wisconsin, Bernard Schwartz, a Two Rivers Business Man, was ready to build a house for his family and gave Wright the opportunity to build his Life Magazine “Dream House”. Bernard and Fern Schwartz made a trip to Taliesin where Frank Lloyd Wright, eager to see the Life Magazine scheme built, was happy to fulfill their dream of owning a Wright designed house. Frank Lloyd Wright modified the Life Magazine plans changing the materials from stucco and stone to red tidewater cypress board and batten and red brick. He went on to refine the design by pushing up the ceiling in the living area making room for a stunning second floor balcony overlooking the sixty-five foot long, aptly named, recreation room. Wright went on to design tables, chairs, hassocks, beds, fruit bowls, lamps and a couch with built-in bookshelves.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Wright’s Usonian vision, first crystallized in his masterworks of the mid-1930s, attained its fulfilment in his Guggenheim Museum, New York, of 1943

The structural idea and parti for the museum date back to his sketch for the Gordon Strong Planetarium of 1925 – a science-fiction proposal par excellence, a ‘ziggurat’ destined for the semireligious gratification of ‘nature-worshipping’ pilgrims. At the Guggenheim, he simply turned the diminishing helix of the planetarium inside out, inverting and thereby converting what had previously been a car ramp into an internal, spiralling gallery, an extended spatial helix which Wright later referred to as an ‘unbroken wave’. The Guggenheim Museum must be regarded as the climax of Wright’s later career, since it combines the structural and spatial principles of Falling Water with the top-lit containment of Johnson Wax. His declaration that the museum was more like a temple in a park than a mundane business building or residential structure may be seen as an ironic reference to the building’s origin in these projects.”[8]

Few buildings have inspired the level of controversy generated by the Guggenheim Museum. In sharp contrast to the typical rectangular Manhattan buildings that surround it, Wright’s museum resembles a white ribbon curled into a cylindrical stack that grows continuously wider as it spirals upwards towards a glass ceiling.

There is no architecture without a philosophy. There is no art of any kind without its own philosophy.

– FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, 1959

The design philosophy : Organic Architecture

Wright has always been driven by the principle that his designs that are in harmony with its surroundings emerging naturally from its context, just like trees in landscape, without falling in mimicry.

At its core, that principle was an aspiration for spatial continuity, in which every element of a building would be conceived not as a discretely designed module, but as a constituent of the whole.[9]

A masterful architectural designer, Wright developed a unique vocabulary of space, form, and pattern that represented a dramatic shift in design from the traditional houses of the day. Characterized by dramatic horizontal lines and masses, the Prairie buildings that emerged in the first decade of the twentieth century evoke the expansive Midwestern landscape. The buildings reflect an all-encompassing philosophy that Wright termed “Organic Architecture.” By this Wright meant that architecture should be suited to its environment and be a product of its place, purpose and time. First developed in 1894, when Wright was establishing his practice in Chicago, this philosophy of design would inform his entire career.[10]

The Falling water project illustrates at he best this approach as the cantilever balconies, mimic the stratified rock of the waterfall below.[11]

Wright was influenced also by the Japanese achitecture and landscapes he witnessed during his trips to Japan. Wright found confirmation of the organic principles of design that he pioneered in his Chicago Prairie buildings which became monuments of a new democratic architecture and great landmarks of American modernism[12]

Wright’s impact in the American architecture was impressive as he achieved to build the ground for a truly contemporany architecture and most of all that emphasise the nesecity that architecture is born as an reflection of a culture and not as a replica of different times.

---------------------------------------------

[1] https://franklloydwright.org/work/

[2] .https://franklloydwright.org/work/

[3] https://www.architecture.org/learn/resources/architecture-dictionary/entry/prairie-style/

[4] https://flwright.org/researchexplore/prairiestyle

[5]https://franklloydwright.org/frank-lloyd-wright/

[6] Kenneth Frampton- Modern Architecture: A Critical History (World of Art)

[7] Kenneth Frampton Modern Architecture: A Critical History (World of Art)-

[8] Kenneth Frampton- Modern Architecture: A Critical History (World of Art)

[9] .https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/checklist/wrights-living-organism-the-evolution-of-the-guggenheim-museum

[10] https://flwright.org/researchexplore/prairiestyle

[11] https://www.archdaily.com/513642/happy-birthday-frank-lloyd-wright