- Permbajtja

- prev

- next

- prev

- next

De Stijl's Rationalism and Abstraction impact in Mies van der Rohe's Crown Hall

by Katerina Lika & Marinela Pjetri, "Thresholds of XX century architecture" EPOKA University

De Stijl's Rationalism and Abstraction impact in Mies van der Rohe's Crown Hall A Dutch art movement known as De Stijl emerged in 1917 in response to the tragedies of World War 1 and focused on using art to rebuild society after the war. As a reaction to the excessively ornamental art-deco style, it was a global visual medium for a new society.

Known also as Neo-plasticism, this art movement valued abstraction and simplicity. This style and philosophy were conveyed via architecture and art in the form of clear, linear vertical and horizontal lines, straight edge, and basic colors. Only the pure fundamental colors, black, and white were to be permitted, and all surface adornment other than color was to be abolished. The underlying concept was functionalism, with a strict and dogmatic concentration on the rectilinear planes, where the structural elements consisting of steel, glass, concrete, and other manufactured materials were to be employed openly and honestly, without mimetic shapes. Despite being a transient trend, avant-garde De Stijl had a significant impact on modern art, architecture, and abstract art. It had a major impact on the International Style, which is evident in the widespread adoption of mass manufacturing, the strong reliance on flat, geometric forms, and the rejection of adornment. De Stij inspired the Bauhaus style with straight lines and simple colours and had its greatest impact on the architectural design of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

One of the numerous milestones where Mies originally used both glass and steel in architectonic structures was Crown Hall , widely considered as his biggest achievement where he initially constructed a large-span universal space free of columns. The parallelism of De Stijl characteristics in Mies’s work can be essentially visible by the simplicity and expressive sincerity of its structural elements. To further analyze the impact of De Stij movement abstraction and rationalism in this particular building architecture this essay will be explored in three aspects following: i) The Grid System, ii ) Building Skin iii) Interior.

The Grid System

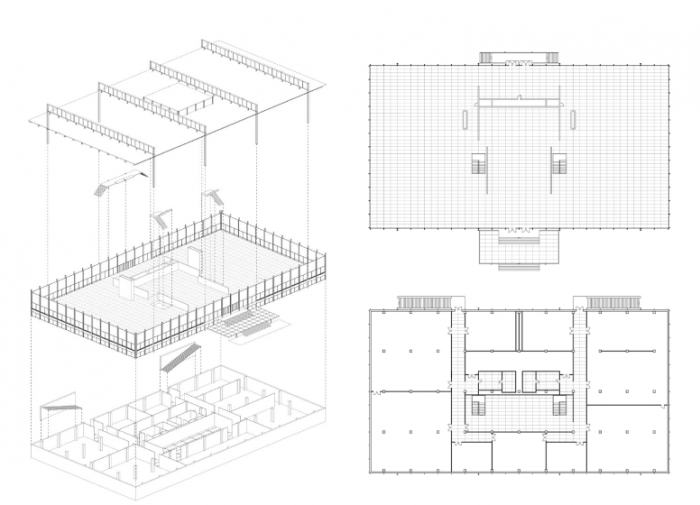

The Crown Hall's plan is a prime example of structural rationalism since it uses a grid system to govern interior and exterior volumes. Functionality is not impacted because the grid's size is suitable to educational standards. This evolutionary perspective gives specific relevance to Mies' shift from the more versatile rectangular plan to the more pervasive square shape. The Crown Hall is regarded as the ultimate example of Mies' architectural beliefs, particularly his support of an honest structural system. The space may fit the furniture it needs, whether it be for a classroom, drawing room, or laboratory, by employing a reverse planning sequence like the grid method. Mies designed outdoor areas that united the purity of a classically planned out institution with the intimacy of the courts. Similar to Crown Hall, where the grid symmetry governs spatial order, but allows for unrestricted movement of structures along the grid. There are no enclosed external areas, allowing individuals to wander around freely, unlike axially clustered plans. The repetitive grid may be seen as a logical navigational language, which allows this idea of mobility to be expanded further. Applying the structure to the grid on a greater scale advances the idea of unrestricted mobility. Internal support is not necessitated, resulting in an open area with unrestrained flexibility and functionality.

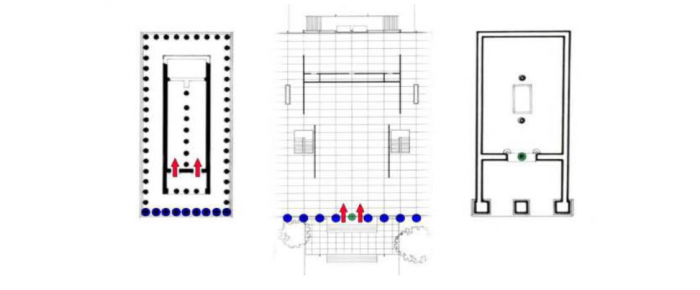

That being said, Mies' initial use of "pre-classical symmetry" is noteworthy since the structural design is reminiscent of pre-classical temples (Figure 1). Because this alludes to Vitruvian aspirations, it is notable that Crown Hall may have been pre-classical architecture modernized for the present. This supports Mies' own development of rationalism.

Building Skin- Façade and use of Materials

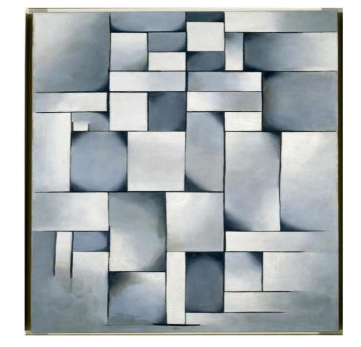

Blake (1963, p. 34) claims that Mies' methods for depicting his idea displayed a remarkable resemblance to the visual techniques used by the De Stijl painters, but this method is also evident in the construction of Crown Hall, not only the drawings. Realistic depictions of the world were rejected by the De Stijl movement. De Stijl abstraction, on the other hand, simplified everything to points, lines, and planes to discover their underlying essence. The structural elements that make up the steel framework of Crown Hall have been used to represent this. Similar to Theo van Doesburg's Rhythm of a Russian dance, Mies unveils the mechanics of the frame by altering the thickness of beams, columns, and mullions before projecting structural parts (Figures 2a).

Figure 2a

Johnson (1978, p. 138), in comparison, contrasts the rational arrangement of the structural parts to that of a Gothic cathedral. The structural honesty notion of Betlage is taken to its logical conclusion in Crown Hall, which exposes the structure from the inside out. The design is conceptualized in terms of steel channels, I-beams, and H Columns, similar to how a medieval design is conceptualized in terms of stone vaults and buttresses, which connects more deeply with classical rationality. The structural framework developed at Crown Hall serves as a model for all modern industrial buildings since it was there that a vast glass-walled, column-free surface was first created, allowing for timeless functionality (Blaser, 2001, p. 9).

His work is distinguished by its geometric composition, complete lack of decorative features, and refinement of the materials (he occasionally utilized marble, onyx, travertine, chromed steel, bronze, or noble woods), all of which were meticulously completed in every last detail. Its ability to utilize a free- flowing area was made possible by the steel frames used in its construction. As a result, Mies created a transparent space which blurred the boundaries between traditionally separated functional zones, drawing parallels with Rietveld‟s Schröder House and expressing Mies‟ own De Stijl influences. The many transparencies that are produced by the interaction of surface and volume on both the inside and outside of the building are a manifestation of De Stijl's presence. The enormous glass panel's continuation turns the top level into a plane that floats above the earth, while the glass itself serves as a gateway through which we may look either within or outside.

The Interior

Crown Hall is described by Blaser (2001, p. 56) as a location where students may feel at home and where the refined tranquil aesthetics lead them back to the fundamentals of design. Johnson (1978, p. 16) gives recognition to Berlage's structural honesty, saying that "all the supporting components should be obvious" and that "those portions of a structure resembling supports should truly support.". This produces an area free of ornamentation where emptiness encourages concentration. Through De Stijl abstraction, the building's structural dynamics and purpose are conveyed. Nevertheless, it is up to the participants of the space to develop their own original and relevant ideas about how they should interact with the environment.

Heidegger's "open region" is represented by the De Stijl abstraction that penetrates into the interior of Crown Halls. The "White plane of the ceilings and gray terrazzo floor plane" are described by Chang and Swenson (Blaser, 2001, p. 21) as defining "the immense light-flooded area. The structural frame is surrounded by essentially uninterrupted white space, with the exception of a "transient sea of student drafting tables," making it comparable to the white space that surrounds De Stijl artwork. Furthermore, although being in a totally open hall of enormous dimensions, the lower sandblasted glass walls at ground level obscure outdoor views to give a sense of solitude. This translucent glass strip and the low partition walls, according to Chang and Swenson (Blaser, 2001, p. 21), imply a "imaginary plane. This describes "a quotidian zone" as a setting where the commonplace daily based activities of teaching and learning take place. The area above this is known as Heidegger's "open region," according to Chang and Swenson (Blaser, 2001, p. 2). The students are introduced to Mies' terminology for contemporary architecture through Crow-n Hall. The Vitruvian triad, which Berlage devised and promotes design as a process of strength, function, and beauty, is referenced in the structural composition and materials. The two distinct working levels of Crown Hall serve as the physical manifestation of what Mies (Blaser, 2001, p. 44) referred to as a "spiritual order." The bottom level serves as a location where students are free to express their creativity via physical craft, whilst the top level encourages them to engage on a metaphorical journey of thinking and design. In order to reinforce his architectural language, Mies' search of structural possibilities allows the exterior and interior to express the same monumentality as the pre- classical structures. The lack of any physical barriers or interruptions in Crown Hall was a deliberate architectural choice. In order to depict the open-spanning construction and unbroken spatial impression, Crown Hall's sole internal walls do not reach the ceiling height. These walls, which are constructed of oak, are the only decorative elements in the structure due to their purely aesthetic attractiveness. IIT Crown Hall was decorated by Mies in this minimalist, abstract manner. The interior rooms clearly incorporate the fundamental colors: orange from the moveable walls, white from the continuous plane surface, and blue from the curtain glass as a final reference to De Stijl inspiration.